Jamdani: a living tradition

Foreword by Saif Osmani, Curator

Muslin Trust undertook 24 oral history interviews with Bangladeshi women residing in the London Borough of Merton who arrived in England in the 1960s and ’70s. These women expressed their cultural heritage by wearing Jamdani textiles and other heirloom saris made in Bangladesh. The 1970s saw the emergence of a new nation amongst the leftovers of Colonial rule and Partition of India, with the East Pakistan period dividing neighbours and friends, so coming together became an innate need for the newly identifying Bangladeshis. Their sense of self and belonging were expressed through the ritual of wearing a Jamdani sari; to reconnect with the culture they left behind, as part of a tradition that extends for over a millennium.

This multi-disciplinary online exhibition includes a film (above), a photo journal (below), interviews, photography and illustrations that capture a key emerging theme of a ‘living tradition’, with 11 further participants, chapter writers and interviews undertaken with people from across London, from Birmingham and Kolkata (India) who have kindly lent us use of their personal photographs. They recall memories of how Jamdani has featured within their own lives growing up, their family relationships, in some cases carrying out their own research and sharing their thoughts on the future of Jamdani. These accounts offer further insight to the original 24 oral history interviews and how Jamdani still holds a special place across multiple generations, as a revivalist movement emerges out of Bengal and Bangladesh.

‘Jamdani’ means flowered motif in Persian, although the roots of this textile are much earlier in South Asia where records have shown that as early as 300AD flowered motifs on fine cotton have been depicted on carved depictions of Hindu gods and deities inside temples. They have been found inside the Moghul courts of the 1600s and used on garments for the English (1600-1900) who had started to bring Jamdani to England. Today flowered motifs are still woven onto fine cotton (muslin) saris and worn on special occasions.

I would like to thank the participants who took part in this online exhibition during what has been unprecedented year and a half that has made us examine what we value in our lives. The 11 participants are: Farhana Akhter, Shaju Bibi, Shahnaz Begum, Mohammed Imran, Alea Ismail, Sarah Ishmail, Shafla Jalil, Sweta Mukherjee, Nasreen Rahman, Sba Shaikh and Rezia Wahid.

The 24 original oral history participants are: Zareen Ahmad, Farida Ahmed, Firoza Ahmed, Mamata Ahmed, Chhaya Biswas, Kawsar Bhuiyan, Begum Rokeya Chowdhury, Hosneara Hussain, Tarana Huq, Momtaz Hoq, Anowara Khan, Rezina Khaleque, Nilufar Khondkar, Jahan Ara Sajeda Malek, Rina Mosharraf, Azadi Rahman, Mahbuba Rahim, Ferdous Rahman, Taleya Rehman, Suraya Rahman, Yasmeen Rahman, Rowshon Rahman, Begum Helena Samad and Rifat Wahhab.

Bringing Jamdani to England has been funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund. The project is supported by London Borough of Merton’s Library & Heritage Services, Museum of London Docklands and the Victoria & Albert Museum.

Project lead: Rifat Wahhab

Written by: Sonia Ashmore

Curated by: Saif Osmani

Photography by: Richard York, Rainbow Collective

Illustrations by: Limma Ali

Special thanks to: Dr Lipi Begum and Jon Klein (filmmaker)

Photo Journal: Bringing Jamdani to England

Read oral histories of 24 participants from the London Borough of Merton:

Image above: Front cover of the photo journal. Click below to download.

“Usually when we go and buy saris, it’s full of work and it’s very heavy. Jamdani is light, so when you put it on you can’t really feel it, it doesn’t feel uncomfortable. If it sits properly and you put it on properly it will stay. It’s one of those saris that everybody’s going to love.”

– Shafla

“I went to Naranyanganj or Sonargaon where the main Jamdanis are handmade, not the machine made Jamdani. So I have seen ‘factories’ of weavers or Tahthi (looms)”

– Mohammed

Photograph album (above): Family members wearing Jamdani (courtesy of participants Farida Ahmed and Zareen Ahmad)

“… during a trip to Kolkata, I discovered fascinating facts: that there was fabric produced so fine that it could slip through a ring…”

– Sba

What is Jamdani?

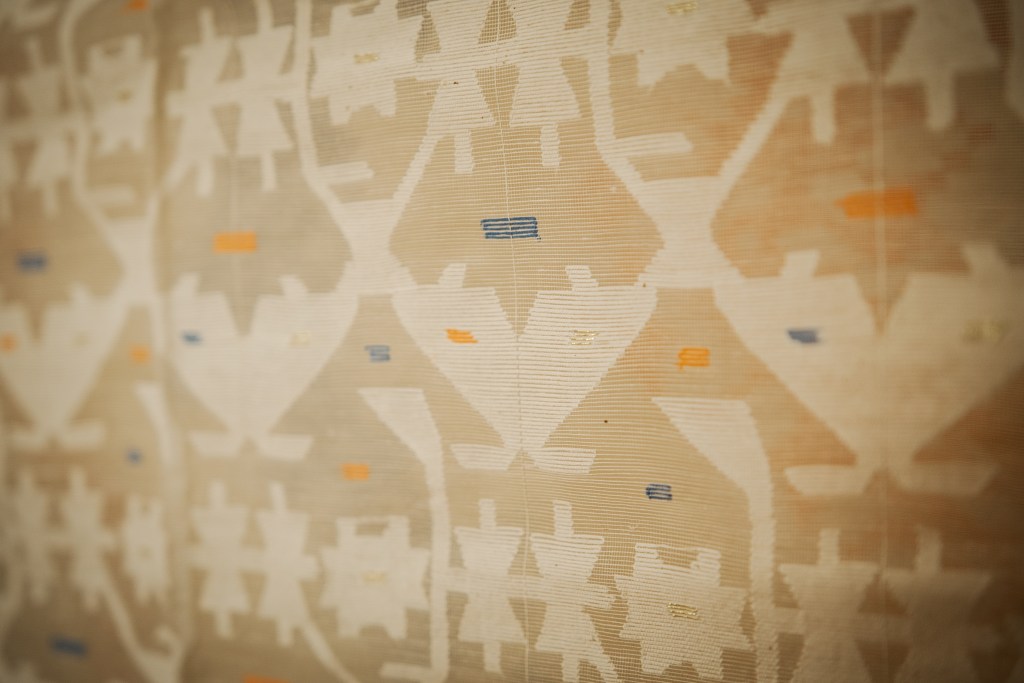

Jamdani is a fine figured cotton muslin fabric woven in simple pit looms in the delta lands around Dhaka, Bangladesh. The quality of the traditional fabric, sometimes as delicate as a shadow, depended on a particular type of locally grown cotton. Weavers evolved a specific repertoire of geometric motifs representing fruit, flowers, leaves and creepers worked in by hand in white, coloured or metallic thread as a discontinuous supplementary weft. One of the supreme achievements of muslin weaving, Jamdani was historically a luxury fabric, requiring intense concentration on the part of the weavers in counting threads to reproduce sometimes tiny regular patterns. Outstanding pieces could take two people six months to weave; recent attempts to reproduce historic Jamdani have taken even longer.

Jamdani muslin was a major commodity exported by the British East India Company more than 300 years before Bangladeshi women brought their own Jamdani saris to Britain. Shiploads of muslin and Jamdani fabrics, once exclusive to the royal courts of India, were imported into Britain from Bengal for fashionable ladies’ dress. As the muslin industry declined, skills were lost through natural and man-made disasters, rice replaced cotton cultivation, synthetic fabrics replaced natural fibres and Bangladesh’s handloom sector was almost terminally devastated by the 1971 War of Liberation. The Jacquard loom has coarsened the traditional motifs and synthetic dyes vulgarised a subtle palette which traditionally used vegetable dyes. Yet the fragile weaving communities and their inherited skills have somehow survived. Today Jamdani is the national fabric of Bangladesh and the cultural significance of this fabric was internationally recognised when it was included in UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2013.

“If I did go back to Bangladesh, I’ll probably still be looking for that unique black and gold Jamdani sari”

-Alea

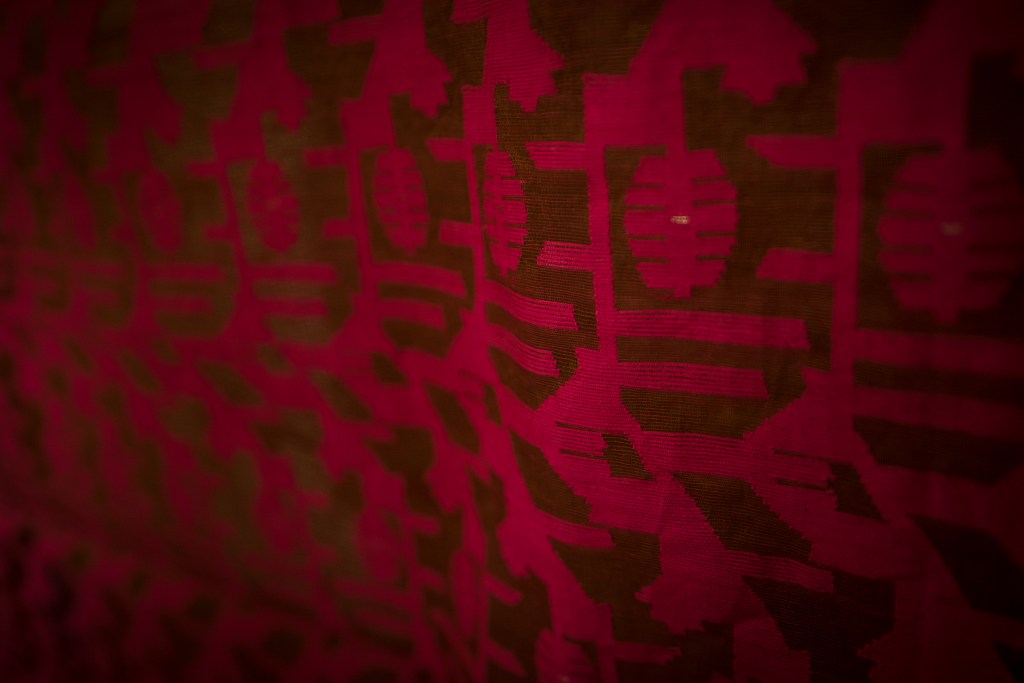

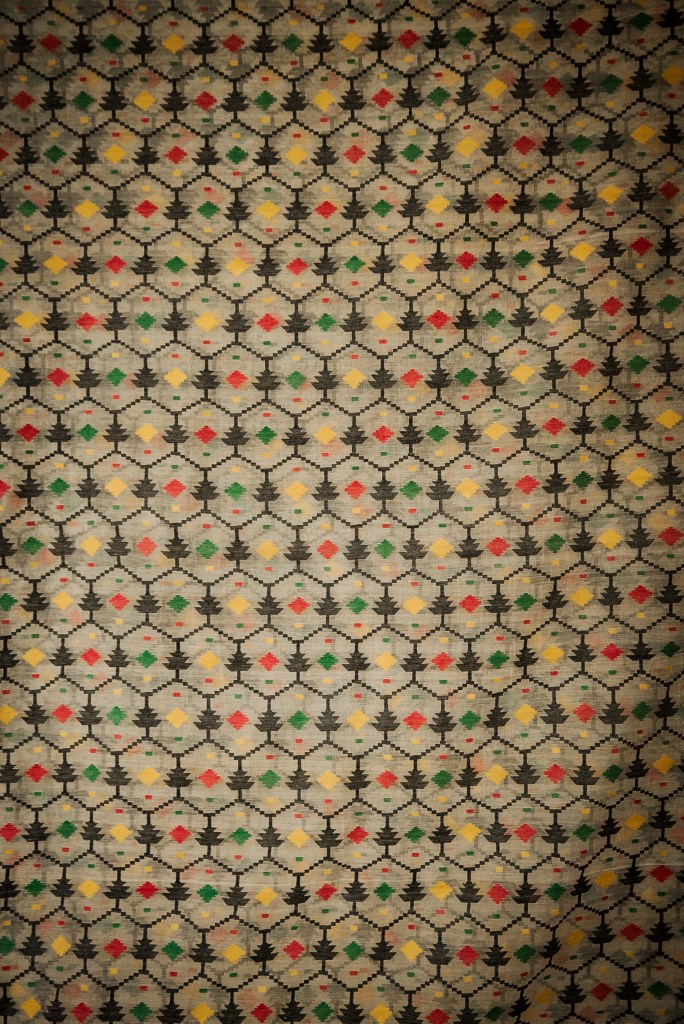

Photographs (above): details of participants’ Jamdanis taken during photography days held at Bell House and Morden Hall Park (2021)

“The magic and the weaving had already happened. And so, what am I going to do by remaking it? At that time I didn’t realise how important history is… how much that weaving tradition had died in the contemporary world”

– Rezia

About ‘Bringing Jamdani to England‘

Textiles can be important cultural symbols and repositories of memory among dispersed peoples. Muslin Trust, with the support of the National Heritage Lottery Fund, has recorded the clothing memories of women who came to Britain in the 1950s, ‘60s and ‘70s and now form part of the Bangladeshi community in Merton, south west London. Arriving in the UK as students, professionals and young wives to join their husbands, many women brought Jamdani saris with them. Some still have these saris in their possession today. They recall how wearing this special sari was an important part of maintaining their cultural identity. At first the UK Bangladeshi population was small and scattered, but as more Bangladeshi women arrived in London, they describe how there were increasing opportunities for cultural and community events where they might wear their Jamdani saris, causing great admiration. As economic circumstances improved, there were more return visits to Bangladesh and women returned with Jamdani saris for themselves, their families and friends. The enduring popularity and appeal of the Jamdani sari among women of all ages is evident within Bangladesh, in the Bengal region of India, and among the Bangladeshi Diaspora around the world.

“My mother and her friends did not buy or wear them as often as they did and soon stopped wearing them altogether. This may have also coincided with the decline of the jamdani sari industry in Bangladesh.”

– Nasreen

Photographs (above): details of participants’ Jamdani saris taken during photography days held at Bell House and Morden Hall Park (2021)

“It’s the memory of sitting on my mum’s lap and the feel of the cotton. ‘Cause obviously when you buy them they’re quite stiff at first then after a few washes they tend to get softer.”

– Shahnaz

Jamdani Stories

There has been migration from Bengal to Britain for more than 200 years. Bengali men, especially from the region of Sylhet, now in Bangladesh, had long arrived as ships’ crews, or ‘lascars’. In the twentieth century, migration was accelerated by the partition of India in 1947, which absorbed Bengal into East Pakistan and in the 1950s and ‘60s a shortage of labour encouraged Bengali workers to come to Britain. The brutal 1971 war from which Bangladesh emerged as an independent nation also caused many to leave their country. Britain became home to part of a worldwide Bangladeshi diaspora.

It was during these later times that women started to accompany, or join their husbands in England. It is hard to imagine the problems of the women in assimilating to English life and the cold climate. They were often very young, newly married and far from the close family units in which they had grown up. Many were well educated and some found jobs soon after arriving, enabling them to mix with non-Bangladeshis. Retaining their Bangladeshi identity was inevitably of fundamental importance. Thus the Jamdani sari has had a culturally important role for migrants from Bangladesh.

While the majority of Bangladeshis settled in East London, a number moved to Merton, in the south west of the city, besides establishing themselves in other parts of the UK. Muslin Trust’s interviews with members of the Merton community of Bangladeshi women have revealed how the Jamdani sari has been integral to their sense of identity and national pride. As one of the interviewees says, ‘When I wear a Jamdani, I know the history from our place. Jamdani is part of our life. Jamdani is my culture, my heritage. It’s social cohesion in a big way.’ In mixed social occasions it turned out to be a way of displaying an exceptional cultural artefact more or less unknown in the West. Furthermore, the Bangladeshi women recognise the skills that go into making Jamdani and the need to support the hand 10 weavers so that Jamdani and its makers have a future. As one of the women says, ‘Everyone should feel proud about it especially those weavers that made them. They are the people who are keeping alive that skill, not only yesterday but generation by generation. And we should not forget about them.’ Muslin Trust’s aim is a modest attempt to support this goal.

“– very bright, bold colours, very delicate, in terms of the material it’s very high-quality cotton muslin fabric, very elegant soft style with lots of stunning, floral and ornamental motifs embroidered, all hand-crafted, hand woven”

– Shaju

Photographs (above): 24 partcipants and their friends show and share their Jamdani saris during photography days held at Bell House and Morden Hall Park (2021)

“Only Bangladeshi textiles are put nicely in a cupboard, in a very special particular way. When it comes to textiles it has to be folded, ironed in a certain way – you can hang them but it was almost always on top of each other. One thing I remember is the way they were all piled up in different colours and different sections.”

– Sarah

“The flowered garments of the finest muslin are Jamdani that originated in Decca (presently Dhaka). It is a loom-embroidered or loom-figured fabric initially woven with diaphanous Decca muslin achieved from the indigenous cotton; Photi Kapas or Gossypium Neglectum”

– Sweta

“Long ago, to see my mum eagerness towards this sari made me curious. I asked my mum what is so special about this sari. She replied that she feels part of a larger community and that in the future I would feel that too. Today my daughter asked me the same as me.”

– Farhana

Bringing Jamdani to England has been supported by: